A rain garden is a shallow planted depression designed to hold water until it soaks into the soil. A key feature of eco-friendly landscape design, rain gardens—also known as bio-infiltration basins—are gaining credibility and converts as an important solution to stormwater runoff and pollution. Here we’ll show you how to make a rain garden fit handsomely into a landscape and still fulfill all of its environmental functions.

Nowadays, according to the EPA, much of the rain that falls on a typical city block heads overland to the nearest pipe, washing along any crud it finds. Historically that water would have infiltrated—soaked in—leaving impurities behind in the soil and plants as it passed through to replenish the water table. Rain gardens are intended to counteract both the unnatural runoff patterns in urban and suburban areas (too many roads, too much paving, too many hard surfaces) as well as the increased crud levels found in them.

Rain gardens can work in most climates, but are most effective in regions with a natural groundwater hydrology—that is, areas with deep soils that drink in water rather than rocky areas that force rain to run overland. Most of the United States is like this. Rain gardens have gained wide residential use in cities as diverse as Kansas City, Minneapolis, and Portland, Oregon (the latter two offer utility-bill discounts for rain-garden installation). Entire towns, such as Maplewood, Minnesota, have turned to rain gardens to handle neighborhood storm-water management, plunking little planted basins down between curbs and property lines.

RAIN GARDEN DESIGN TIPS

- Think of a rain garden just like a border or foundation planting rather than a beloved specimen tree. In other words, it should not be a stand-alone feature.

- Consider all the rules of composition, screening and circulation—not just the rule that says to put a rain garden in a low spot 10 feet from the house.

- Pick a shape that works with the rest of your garden design. A rain garden does not need a specific shape to function properly so feel free to be creative.

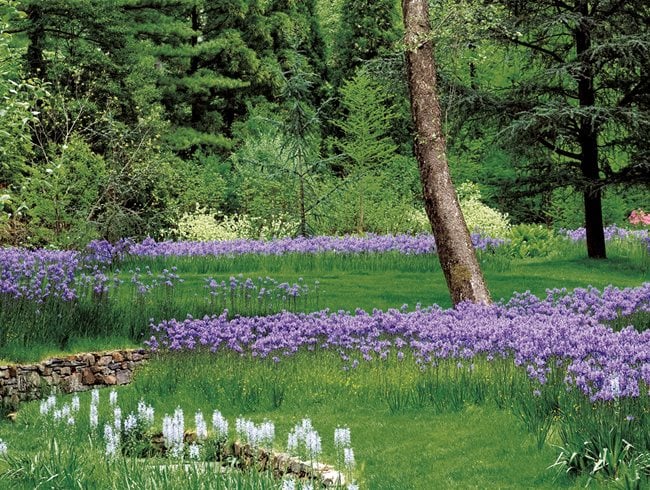

- A rain garden can be as formal or as wild as you like—it’s all about the plant selection. Monocultural rain gardens are OK as long as that fits with your overall design. Here are some favorite rain-garden plants: Lobelia cardinalis (cardinal flower), Iris versicolor or I. virginica (blue flag iris), Veronicastrum virginicum (culver’s root), Carex vulpinoidea (fox sedge), Cornus sericea (red-twig dogwood), Acorus gramineus(sweet flag), and Athyrium filix-femina (lady fern).

- A rain garden doesn’t have to be separate from other plantings. Consider making a depression within a perennial bed or shrub border (especially if space is tight and you don’t have room for a larger rain garden that stands alone).

- Put in more than one rain garden for repetition and continuity. If it works with your overall design, create a little rain garden for each downspout.

“So how can we get away from a rain garden being a kidney shape plopped in the front yard?” asks John Gishnock III. My thoughts exactly, because that result is pretty common. Gishnock is owner of Formecology, a design/build firm specializing in rain gardens and native plants in Wisconsin. He has created rain gardens that are seamlessly incorporated along typical suburban driveway-to-door sidewalks; gardens below dry-laid stone walls adjacent to rustic pathways; and even a garden in the shape of a spiral galaxy (to be viewed from a lucky owner’s second-story porch). “A rain garden,” says Gishnock, “needs to look like the rest of the landscape.”

Landscape architect Jim Hagstrom of Savanna Designs in Lake Elmo, Minnesota, agrees. “We integrate rain gardens into the design,” he says, “and two-thirds of the time you won’t notice them.” His designs depend mostly on his clients’ sensibilities. Some love the wild native look of a traditional rain garden, while others favor the idea of infiltration but don’t want to see a “patch of weeds.” He has incorporated a rain garden into the center of a circle drive and devised a standing stone flow-through curb to match the house. He has created a large basin that infiltrates most water then holds the rest for pond habitat. He has built rain gardens in the centers of lawns, by dishing the landscape and ensuring well-draining soil. “You get a little pond after a rain,” he describes, “and in 24 hours it’s gone, and you have the lawn back.”

However they look, rain gardens work, helping to reduce storm-water waste by 99 percent, according to one study, and keeping runoff clean. But they can also be an integrated design element, making landscapes both sustainable and beautiful.

This article was written by Adam Regn Avidson and published in April 2019, on GardenDesign.com: